Sigma

Sigma Sigma

Sigma

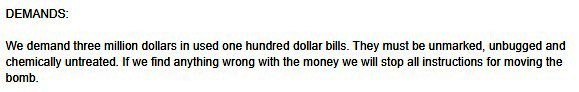

On August 26, 1980, a thousand‐pound bomb exploded at Harvey's Resort Hotel on the south shore of Lake Tahoe. The bomb had been placed in the casino's 2nd floor executive offices as part of an extortion plot demanding $3 million from the casino's owners.

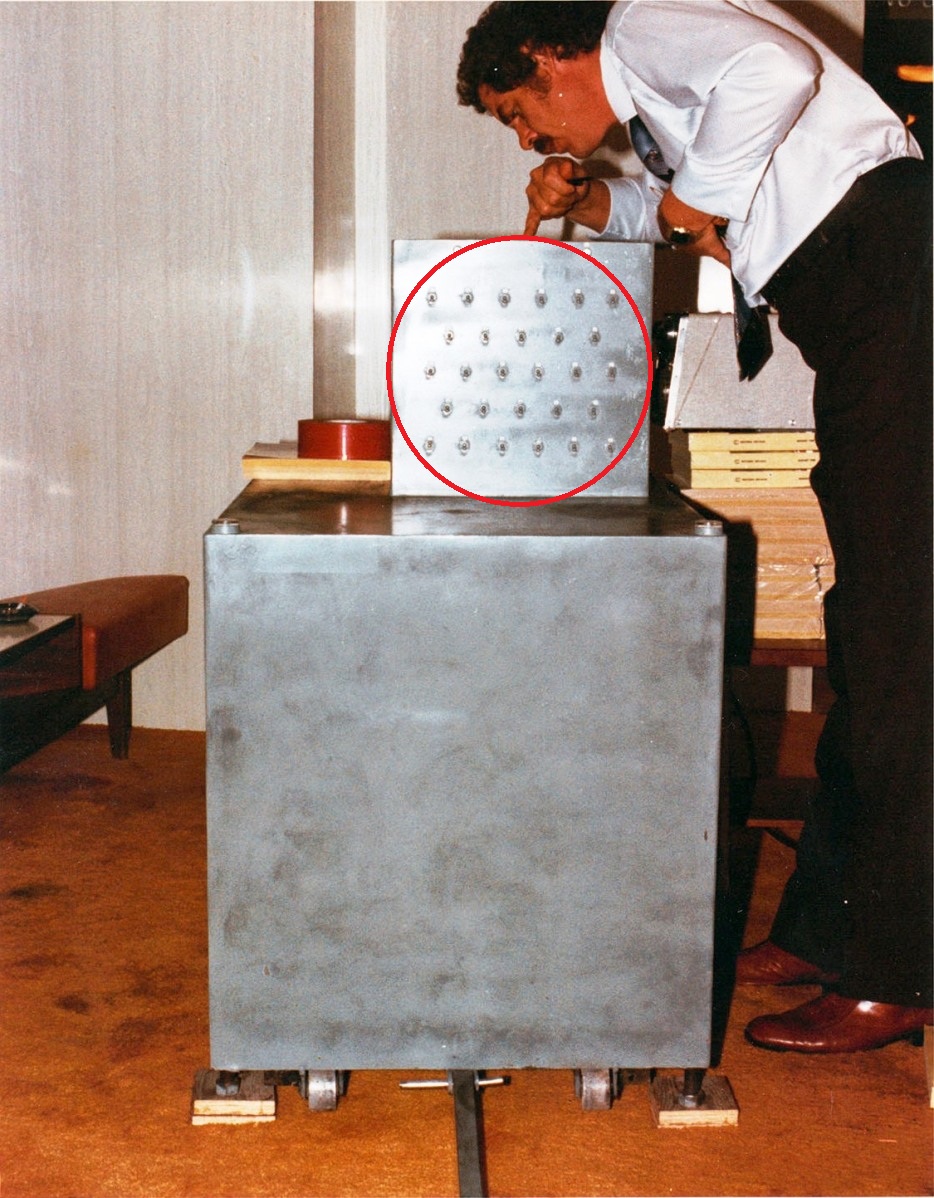

The bomb was a highly sophisticated, tamper‐proof device and was inside a metal box weighing over 1,000 pounds. It was designed with eight triggering mechanisms, making it nearly impossible to disarm. The bomb also contained a 28 toggle switches, and if the wrong one was flipped, the device would detonate.

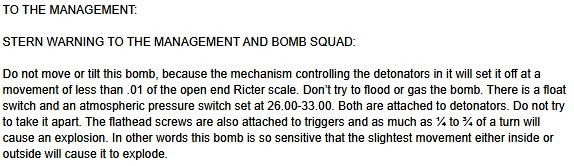

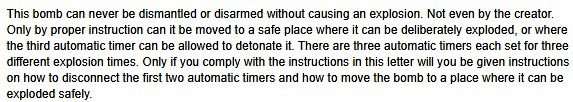

John Birges Sr., a disgruntled gambler, had lost hundreds of thousands of dollars gambling at Harvey's and orchestrated the plot. Birges saw extortion as a way to recover his losses. He and his accomplices delivered the bomb and a three-page ransom letter detailing the demands. He warned authorities not to tamper with the device.

At first, the FBI tried to pay the ransom, but a series of screw‐ups on both sides meant that the money was never dropped off at the designated drop point. It appeared that the bomb, besides all the motion detection and disassembly traps, had a at least one timer that would trigger the device after some amount of time that was unknown at the time.

The FBI and bomb squad attempted to determine how to disarm the bomb by x‐raying it. Yet, the design was too complex. With the help of Livermore Labs, it was thought that a shaped charge could shear the top compartment (which contained the toggle switches) that appeared to control the bomb. It turned out that the top compartment also had some amount of explosives in it, which triggered the main casche of explosives in the lower, larger compartment The blast completely destroyed the second floor of the casino, causing $18 million in damage. Miraculously, no one was killed or injured, as the building had been evacuated.

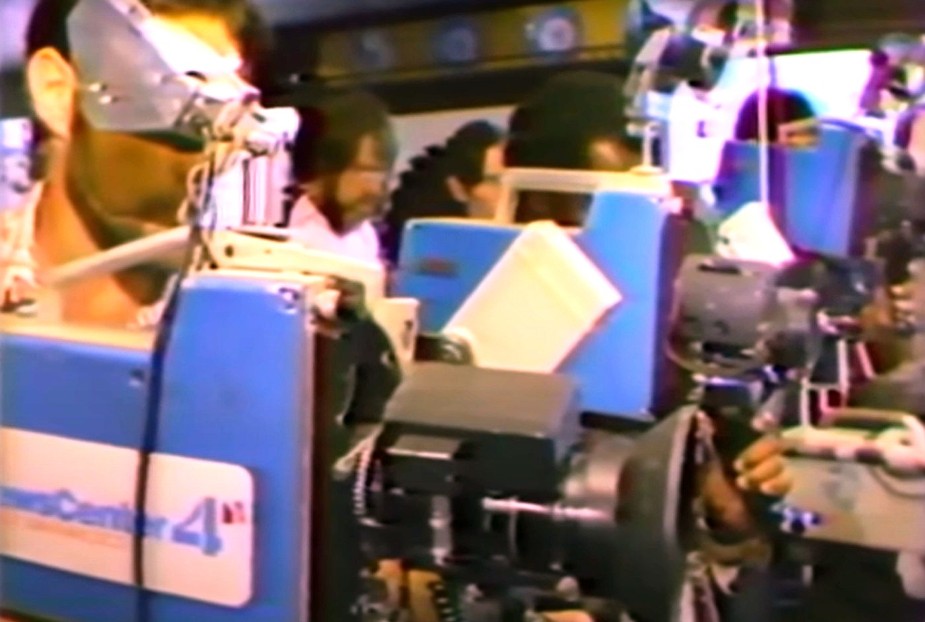

While I played a small part in the logistics of rigging up what follows, that is not my actual connection to the story. I was one of the few maintenance engineers on duty that day. I happened to be in master control when the operator answered the phone. He politely told the caller that he needed to talk to a supervisor, and while that wasn't me, he handed me the phone anyway.

I don't recall where the supervisor was, but at the moment he was not there. Before I actually got the phone to my ear I could hear the person yelling. The essence of the conversation, excluding the profanity, Was. "Did we have any idea of what we were doing?" I responded with something to the effect of "What are we doing?" It continued along the lines that if we are an NBC affilate, which KCRA was and is, why were we feeding ABC, a competing network, as well.

What brought forth that phone call from a very pissed off producer, so he said, in New York?

At the beginning of the 80s, almost all stations doing news had microwave vans or trucks. On flat ground I've seen signal paths as long as 70 miles. From a mountain peak I've seen signal paths of 100 miles. Depends on the power used, and the atmospheric conditions.

Satellite transmission for news coverage in 1980 was not yet practical. While networks utilized what was called the C-band of frequencies (2-4 GHz) on fixed dishes or foldable dishes on trucks or trailers, the expense ment that most local news gathering remained out of reach. Besides the 10-15 foot dishes for the C-band frequencies the power required made transmitters expensive, large, and not practical to be running around like the microwave trucks could do.

Also, another required element, the geo‐synchronous satellite were quickly growing in numbers in the early 80s. The geo‐synchronous satellite has a orbital period the same as the Earth's rotation period, making the satellite appear to be motionless to an observer on the ground. This made reliable, and much more simpler satellite uplinking and receiving reliable. Its no coincidence that the same year this story was taking place, CNN started using one of these satellites. Many other "cable" networks also sprung up in the early 80s. Satellite technology was new enough and exotic enough at that time that you needed a license not only to transmit using a satellite, You even needed a license to receive the satellite signal. Why? Networks and cable companies feared that without licensing, businesses or individuals could freeload on expensive satellite content.

In 1983, Hubbard Broadcasting, a group owner of TV stations partnered with NBC and the manufacturer M/A-COM to develop and deploy the first Ku-band satellite news truck. Ku-band satellites had higher frequencies (12-18 GHz) that allowed for smaller, more portable dishes. They also helped develope the infrastructure so that once the truck found the correct satellite, it had communications channels that allowed the truck to talk to the satellite operators, and those operators would call into a auto‐answer phone line that TV stations using the service would setup to provide audio feedback to the truck operator, and the talent on site. In the mid-80s "portable" phones where the size and weight of a brick. ABC & CBS soon followed with simalar systems. Early on the Hubbard Conus system was the most user friendly.

But this was happening in 1980, four to six years to soon. So how do you get a microwave live shot out of South Lake Tahoe. The problem: Lake Tahoe sits at an elevation of 6200 feet. It is completely encircled by ridges of about 10,000 feet. The answer: A helecopter. At the time only KCRA had one in the Sacramento market. But while necessary to pull this off, it was not sufficent. To clear the 10,000 foot ridge between Tahoe and the Sacramento area the helicopter had to be at almost 12,000 feet in altitude. That's almost 6,000 feet above where the action was taking place. Most ENG cameras at the time had 10 to 1 zoom lens. A camera zoomed in all the way at that altitude would still be no where near enough to show much worthwhile. Plus zoomed in all the way in a moving helicopter it would be a shake‐fest.

Why was the helicopter moving? At 12,000 feet of elevation the air is not thick enough to keep the helicopters engine cool enough if it was stationary. So it had to keep moving. So to pull this off, we need a helicopter. Check. It has to be moving. Check. But since its camera shot from the chopper would still be a very wide shot of the action, needed to get a more local camera shot up to the helicopter. Hum!

So the station decided to use a portable 13GHz microwave transmitter and receiver, each about the size of a lunchbox. These work over a distance of a few miles. The receiver was mounted on a camera tripod attached to the chopper. The transmitter was on a camera tripod, near the camera shooting the action. Simple rifle scopes were mounted to both the transmitter and the receiver. The person at the chopper receiving end used the sight to point towards the transmitter on the ground. The person at the transmitter on the ground would keep the helicopter in their sight.

What could go wrong! The FBI and local responders informed everyone before they used a shaped charge explosion to separate the upper box from the bottom. So since the helicopter had to keep moving, it flew an oval racetrack pattern. The chopper had three microwave antennas mounted to the bottom of the craft. One was an omni radiator. Its signal traveled out in all directions. So its signal was only good for 10‐20 miles. It wouldn't make it back to Sacramento. The other two antennas were referred to as "launchers." They resembled skinny missiles. They were in reality very high‐gain antennas. One faced forward, and the other aft. So whenever the chopper was facing towards or away from KCRA's receive site, it could use either one to send the signal back. When it was in a turn at either end of its oval track, the signal was lost. So the pilot, well‐known and long‐time pilot, reporter, and producer when needed, Dan Shively had to time his "racetrack" positioning with precision.

So as the time neared for the attempt to disarm the bomb approached the stage was set for my phone conversation with NBC NYC.

So let's talk about how you moved most video across the country in 1980. It was via "Ma Bell." To move video, it was either via microwave or physical coax. The only people at the time that had those coast to coast were the Bells' long‐lines nationwide network. There was not a satellite uplink facility in Sacramento at the time. So it had to be via the Bell system. Now, while most broadcast facilities had wideband connections to the local Bell Central Office, they normally weren't set up, or provisioned, as they would say, to take a video feed out of a station and send it anywhere.

If KCRA wanted to send video back to NBC NYC, it would have to request that the Bell System set that path up. Usually, that took a couple of days. The saving grace here is that NBC carried far more weight here than KCRA could ever have, because it was the Bell System that distributed NBC's (and the other two alphabet networks of the time) programs to all its affiliates. So in short order, Bell managed to create a video path from Sacramento to New York.

But how did ABC get into the picture, no pun intended? At the time of the phone call I hadn't a clue. NBC paid for and thought they had exclusive video of the moment the attempt to disable the bomb only to see that rival ABC had the same video. Did Ma Bell somehow screw up? No. No one considered the geometry of our helicopter microwave link. It links the helicopter to our site in Walnut Grove. This place is about 20 miles south of Sacramento in the Sacramento Valley.

If you plotted the signal path from South Lake Tahoe to Walnut Grove, and extended the path as you see above, you would hit Mt. Diablo. This is in the northeast edge of the San Francisco Bay area market. Some San Francisco stations had facilities up there. One was KGO. KGO is not only an ABC affiliate, but ABC also owned it. It was what is known as an O&O (Owned and Operated by the ABC network). At this time, no company, including the networks, could own more than five stations.

As an ABC O&O it not only received signals from the network; it had a permanent connection between KGO and KABC and the network's West Coast network hub in Los Angeles. From there ABC has permanent connections back to New York. Also at the time (I think this is still true today), KGO and KCRA had news‐sharing agreements. This meant that KCRA could use KGO news content, and KGO could do the same with KCRA.

KGO knew what KCRA was planning to do, so when the time came, they swung a microwave receive dish toward the South Tahoe area, allowing ABC to see the same video that NBC was receiving.

A couple of interesting, and one ironic, parallels to Mt. Diablo. It had such a commanding view of a large part of Northern California that when they started surveying the northern part of the state, they made its peak their central datum point. There is a major street in San Jose called Meridian, because that street is directly south of the mountain.

When the station in Sacramento that eventually became the ABC affiliate first went on the air, they put their first transmitter on top of that mountain, even though it is technically in the Bay Area market, it still had an excellent ability to cover Sacramento, Stockton, and Modesto. Those other two cities originally had licensed stations of their own, but now are folded into the Sacramento market. To become an ABC affiliate, ABC made them move their transmitter away from close proximity to their KGO station. That move prompted a concentrated orientation of TV transmitters in the Walnut Grove area. I have a couple of articles about KGO and other near

affialiates, and the

tower

that had the receiver that KCRA was using for the Tahoe shot.

Eventually they caught up with the culprits. The Harveys' Casino bombing remains one of the most infamous bombings in U.S. history. It showed how complex homemade explosives can be and the challenges of disarming them. The case is still studied in law enforcement training today. The bomb was booby‐trapped very well. The makers said even they couldn't disarm it. They could only give a way to move it safely for detonation.

When collecting my thoughts on this story and researching my recollection of this, I found this very interesting and complete documentary done by KCRA on the bombing:

Bringing Down the House: The Bombing of Harvey's Casino