Sigma

Sigma Sigma

Sigma

In another article, I talked about my time at Xerox. Xerox was a good company to work for back then. They offered great benefits and treated me well. I can't comment on the present situation, though. The pay wasn't good. When I started a family, I was the main earner. So, I knew I needed a career that would earn more money.

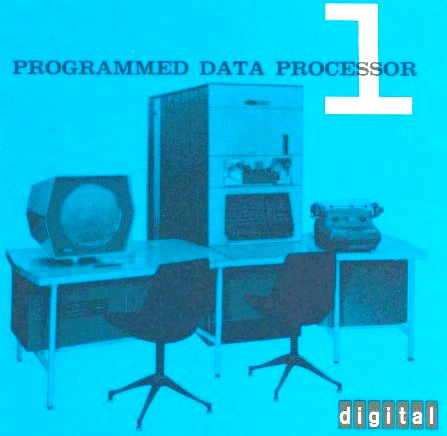

Even after leaving Xerox, I kept friends there. I continued to follow the company's journey in copiers and other endeavors. My travels in the tech world introduced me to microprocessors and minicomputers. My interest in "minis" was piqued when I read the book "The Soul of a New Machine." Its author, Tracy Kidder, garnered a Nobel Prize for the book. It tells the story of Data General (DG) and their race to catch up with Digital Equipment Corp (DEC) in the 70s. DEC had launched a 32‐bit computer, while DG still only offered 16‐bit ones. Some may find the book dull. However, those who have worked hard to bring a new idea to life will feel its drama and frustration. This is true even if you're just part of a small piece of the design. I read the book cover to cover several times.

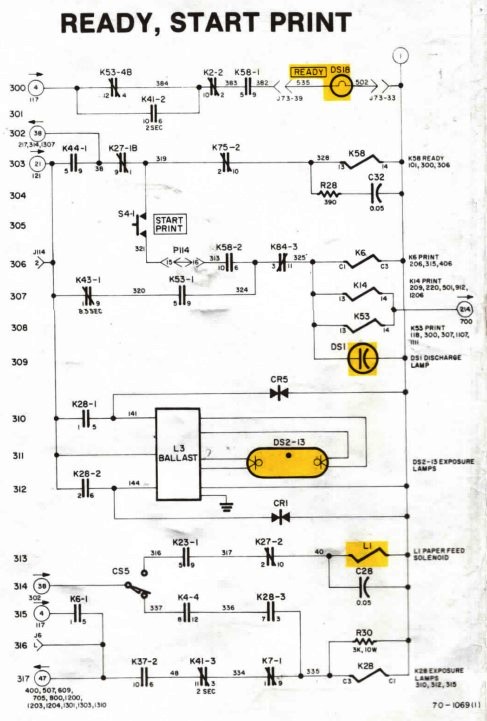

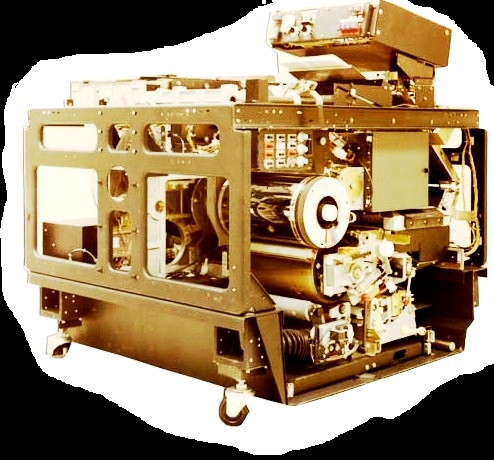

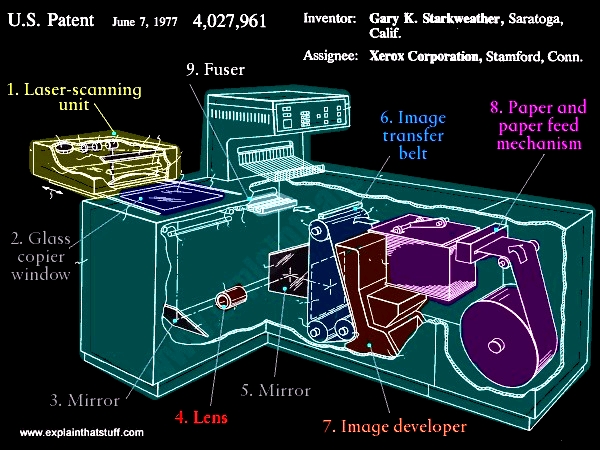

I spent time in computer centers waiting for my batch job to run on the school's IBM 360 for a class assignment. I never really interacted directly with a mainframe. But at Xerox, I was trained on a couple of machines that copied computer printouts, and one that could take the actual output from a mainframe, and "print" it. While trained on it, I never took an actual service call on one. You can see a article I wrote about it here.

But being around places where large high‐volume copiers lived exposed me to lots of IBM hardware. At one point in time, Xerox dabbled in IBM's territory, and IBM did the same with Xerox. An urban legend at Xerox says that an IBM exec arrived with a few minions at the Xerox Tower in downtown Rochester, NY, also known as "the toner palace." He asked for an immediate meeting with the top executive in the building. I don't remember if that was C. Peter McColough or not. McColough was President of Xerox at the time. The "IBMer" proceeded to hand the Xerox guy a set of manuals. They were the manuals for the soon‐to‐be‐released first second‐gen copier, the 9200. Someone, most probably disgruntled, had mailed a copy to IBM HQ in Armonk, NY.

Anyway, besides having a long interest in Xerox, DEC, and Data General, I also had one in IBM. At some point, I came to see that Xerox, DEC, and IBM shared something. They had more in common than their occasional rivalry. All three put their respective industries on the map. Let me tell you how this is so.

The mini‐computer niche turned out to be short‐lived. By the 1980s, PCs (like the IBM PC and Apple II) rapidly cannibalized the mini‐computer market, leaving no time for diversification.

One reason was commoditization. The microprocessor collapsed the hardware cost/performance hierarchy.

A second was failure to adapt. Most minis didn't transition to networked environments or GUIs fast enough. Kenneth Olsen, founder and then President of DEC rejected a couple microcomputer projects in 1977. He was reported to have said "There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home." In 1982 after IBM launched their PC, hurriedly DEC launched three incompatible machines to compete with IBMs DOS. Each had its own proprietary architecture. The growing software development community steered clear of the machines. DEC itself didn't make writing software for the machines a priority, as it was worried about cannibalizing its existing software market for its earlier machines.

In the 90s DEC was struggling with coming out with new architecture to continue their success with their high‐end VAX and VMS lines. They also introduced the first 64‐bit microprocessor chip.

DEC was bought by Compaq in 98, which was bought by HP in 2002. Data General played in the PC market for a while, but mainly concentrated on Unix machines. It was eventually sold to EMC. Others simply shut down. Today the mini‐industry only lives on in architecture.

vents weren't a whole lot nicer to the microcomputer industry than they were to the mini‐computer industry.

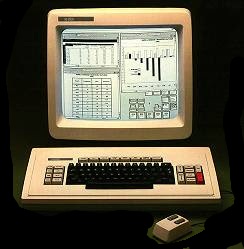

Much has been written about how Xerox invented the PC and did nothing with it. Xerox tried to invent the future, and it did, spectacularly. At Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), its engineers created technologies that would change the world:

But Xerox was focused on protecting its copier cash cow, largely failed to commercialize these ideas. In one of corporate America's most legendary missed opportunities, it was Apple, Microsoft, and others who ran with PARC's inventions, not Xerox.

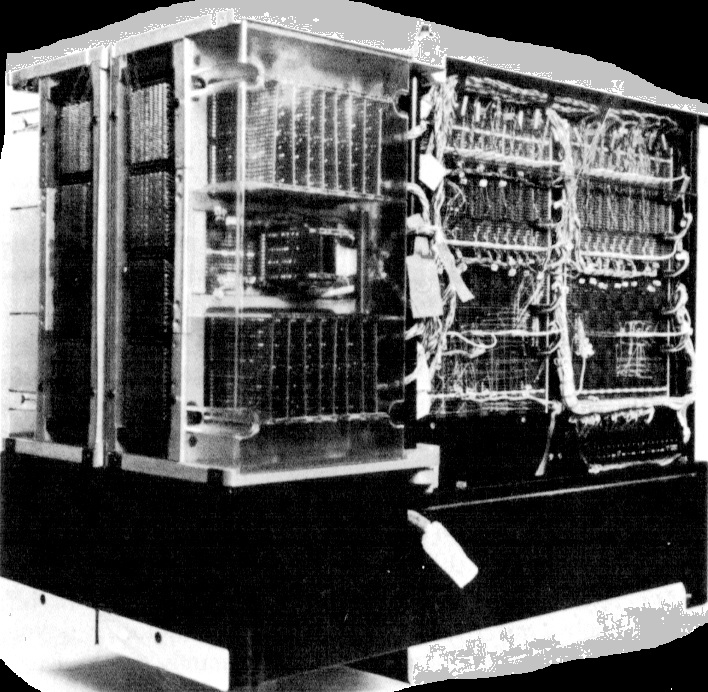

In the broader tech world, IBM loomed like the "environment." It was so dominant that even as Xerox, Apple, and others developed personal computers, IBM's entry into the PC market in 1981 felt inevitable. IBM lent credibility to the entire personal computing industry. But PCs, once exotic, were destined to become commodities, manufactured cheaply, sold everywhere, differentiated more by marketing than technology. IBM's mainframes, on the other hand, adapted and endured. Today, they still quietly run huge parts of the global economy, banking, airlines, and logistics. Far removed from the now disposable laptop world.

And Xerox? Though it faded from the consumer spotlight, it never disappeared. Today, Xerox operates as a major player in IT services, workflow automation, and document management, fields it helped pioneer decades ago. The company that invented the copier and, arguably, the personal computer, continue to evolve, focusing on digital transformation for the modern workplace. In a sense, Xerox has come full circle: still supporting the information revolution it helped launch. Just not always in the ways anyone expected.

Although Xerox fell off the PC tiger early on the others in the market soon found that from the beginning, the personal computer was destined to become a commodity.

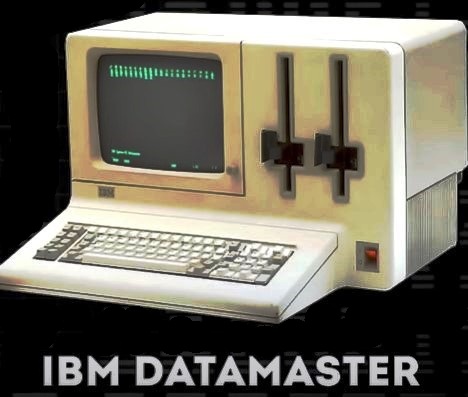

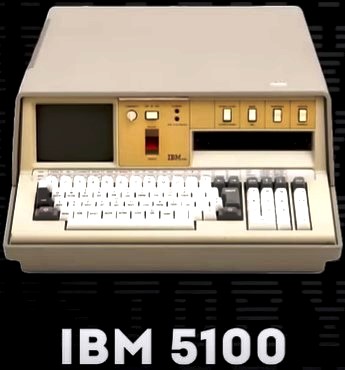

Unlike mainframes or even early minicomputers, PCs were built from standardized parts. Processors, memory chips, disk drives, and monitors. These were modular components made by a growing web of suppliers. IBM's decision to use off‐the‐shelf parts for the original IBM PC (instead of custom‐building everything the way they did with mainframes) set the stage. And when IBM also allowed the operating system (Microsoft DOS) and hardware architecture to be licensed or copied, it kicked the door wide open.

Suddenly, anyone with manufacturing capacity, from Compaq to Dell to Gateway, could build "IBM‐compatible" machines. Costs dropped, competition soared and features quickly leveled out. Price became the main battleground.

At the same time, software, not hardware, became the real differentiator. If every machine could run the same programs: WordPerfect, Lotus 1‐2‐3, and Windows, then the hardware itself became less special. Customers started shopping based on price and service, not innovation.

Laptops followed the same path. Early models were exotic and wildly expensive. But as battery technology, displays, and chipsets matured, building a decent laptop became something many companies could do. Standardization around platforms like Windows and Intel processors pushed laptops down the same commodity chute.

In short: A commodity market =

standard parts + standard software + open competition

No matter how cool or advanced a PC seemed at first, the economics of scale and open standards always pointed toward mass production and price wars. Most PCs became indistinguishable inside, using Intel chips, Microsoft Windows, and off‐the‐shelf parts. That's why today you can buy a laptop for a few hundred dollars, and why only a few companies (like Apple) manage to escape pure commodity status by building their own ecosystems.

Meanwhile, mainframes remained specialized. They are complex, high‐end systems that were tightly controlled and customized for critical enterprise applications. That's why IBM's mainframe business persists today, even while its old PC division was sold off long ago. Lenovo bought IBM's PC division in 2005, gaining the ThinkPad brand.

With the PC the margins shrank. Only the most efficient manufacturers (like Dell with its direct sales model) could survive. Smartphones and tablets reduced consumer need for home PCs. The shift to cloud computing and enterprise services moved the value away from commodity hardware. That meant that only companies with diversified portfolios or scale survived.

Today only Apple, Dell, HP, Lenovo Acer & ASUS survive. So today (again except for Apple) Efficiency beats differentiation. Enterprise services, software, and ecosystems matter more than boxes. Consolidation is inevitable when growth slows, and margins shrink.

The other two segments: Different but still alive

Mainframes became the cloud, and copiers became digitizers, tied into cloud‐based storage, workflow, and collaboration systems. Both now serve the information lifecycle, not just paper or compute cycles.

PCs cannibalized both minis and terminals. Then mobile and the cloud cannibalized the PC.

Yet PCs remain critical for productivity, engineering, and hybrid work. The PC evolved into a node in the network/cloud environment. The future of the PC? Laptops and tablets will dominate but possibly become more modular/cloud‐connected. There is a growing split between consumer‐grade PCs and pro/creator machines.

This is the Information Ecosystem. In the beginning all three were early attempts to manage and process information, whether on paper or digitally.